New Horizons is the first spacecraft ever to travel to the dwarf planet Pluto. The main objective of the mission is to observe the distant Pluto for the first time as well as photograph the five known moons Charon, Nix, Hydra, Kerberos, and Styx, and perhaps some moons not yet discovered.

New Horizons was launched on January 19, 2006 from Cape Canaveral, Florida. As it escaped Earth's gravity, it reached a speed of 36,360 miles per hour or 10.1 miles per second! Shortly after launch, it passed the moon, and by April 7, 2006, it had passed Mars's orbit. Soon after, in May 2006, New Horizons passed into the asteroid belt. It is true that there are many asteroids in the belt, but they are very far apart. The closest flyby of New Horizons to an asteroid was 132524 APL at about 60,000 miles on June 11-13, 2006, and the probe took this opportunity to test its instruments. However, at risk for damaging its instruments by looking at the Sun, New Horizons did not unveil its more powerful telescope, LORRI for this distant flyby.

New Horizons's pictures of the distant asteroid 132524 APL. The diameter of this asteroid is estimated at about 1.4 miles.

By late October, New Horizons had left the asteroid belt and was on target for its flyby of Jupiter. In early January 2007, New Horizons began its Jupiter encounter. As New Horizons passed Jupiter, it tracked and took photos of Jupiter's outer moon, Callirrhoe as practice for navigation. Also, New Horizons made observations of other of Jupiter's moons and edited their orbit information. On February 28, 2007, New Horizons passed its closest to Jupiter at about 1.3 million miles from the planet. On March 5, the Jupiter encounter came to an end.

On June 8, 2008, the probe passed Saturn's orbit. On March 18, 2011, New Horizons passed the next planet, Uranus. On December 2, 2011, New Horizons's distance from Pluto dropped below 983 million miles, the closest approach to Pluto ever by a spacecraft. This surpassed Voyager 2's record set in the 1980's, although this mission was not directed toward Pluto. In 2012, New Horizons began a series of simulations to test equipment for the Pluto encounter.

In 2013, analyses on the Pluto system assessed growing concerns that the many moons of the Pluto system suggested the presence of other extraneous debris - in other words, a possible threat to the spacecraft. The current planned trajectory takes New Horizons to a relatively safe area, namely near the orbit of Charon, Pluto's largest moon and its binary companion. The reason that this was theoretically safer was that Charon, being large, clears the debris in its orbit with its gravity, unlike its smaller satellite neighbors. However, just in case a closer look revealed danger, alternate flyby plans were devised. Later analyses concluded that the risk was not significant and that New Horizons could proceed as planned.

In July 2013, New Horizons was close enough to distinguish Pluto (bright spot at center) and its largest Moon Charon (dim spot just above and to the left of Pluto).

On its path towards Neptune, New Horizons approached the Neptune's

L5 point in late 2013, allowing the spacecraft to take a few observations of recently discovered asteroids near that location. On October 25, 2013, New Horizons became less than 5 AU (astronomical units) from Pluto.

On August 25, 2014, the probe passed Neptune's orbit, at which point it was only about 2.5 AU from Pluto. On December 6, 2014, the spacecraft emerged from its final period of hibernation before the Pluto encounter. Over the next several weeks, the operations team checked the functioning of the system's instruments.

During the final approach, image resolution improved steadily. By early February, New Horizons was able to discern both Nix and Hydra, two of Pluto's smaller moons (though Styx and Kerberos are smaller still).

In the above image, Hydra is highlighted by a yellow diamond and Nix by an orange one. The lefthand image shows the Plutonian system and background stars, while the right has been processed to emphasize the Moons. The bright streak in each image is an artificial effect of the camera resulting from overexposure of Pluto.

On March 10, New Horizons passed its final symbolic milestone as it became less than 1 AU from the dwarf planet - closer than the Earth is to the Sun. New Horizons also realized its first color image of Pluto and Charon on April 14, 2015.

The following month, images from New Horizons became the best ever looks at Pluto. During June, the probe revealed reflective polar regions, dark spots and other tantalizing features of Pluto as well as on Charon, also capturing the massive difference in coloration between the two objects. Some of these features appear in the image below, taken between June 25 and June 27.

On July 14, 2015, at precisely 11:49:57 UTC, the New Horizons spacecraft made its closest approach to Pluto at a distance of 7,800 miles (12,500 km). During the flyby, all instruments were busy collecting data, so it was only hours afterward that the probe sent a signal to Earth confirming the flyby's success. After an additional 4.5 hour delay for the radio signal to travel, news of the mission's success reached Earth over 10 hours after closest approach. New Horizons took the following path through the Pluto system:

The above image shows the positions of Pluto and its moons when New Horizons made its closest approach (C/A). After closest approach, the probe briefly passed into the shadow of Pluto and then of Charon, allowing it to observe how sunlight interacted with the bodies' atmospheres.

The first image, taken before the Pluto flyby, shows the never-before-seen world in true color. The photograph, with its iconic heart-shaped feature, became one of the most famous images captured by a spacecraft. The second image shows the mostly gray coloration of Charon as well as its reddish polar cap.

The analysis of Pluto's atmosphere (primarily conducted as New Horizons passed behind the shadow of Pluto) indicated that it was dominated by nitrogen, and that this nitrogen escaped the relatively weak gravity at a rapid rate. This fact, added to the observed complexity of the surface's texture and composition from enhanced-color imagery, indicate that Pluto is geologically active.

In August, NASA identified the Kuiper belt object designated 2014 MU69 as the next target for New Horizons under the constraints of its diminished fuel supply.

Meanwhile, data from the Pluto encounter continued to produce astonishing discoveries. For example, the occultation images showed that Pluto's outer atmosphere is in fact a blueish color, an effect caused by the scattering of sunlight off of complex molecules. These molecules form through the interaction of nitrogen and methane with solar wind.

In addition, surface analysis revealed the presence of exposed water ice on Pluto, indicated in the image above. All of this analysis and more was completed before New Horizons even finished transmitting data from the Pluto encounter. Due to the limited power supply on the spacecraft as well as other factors, the images and instrument readings that were all collected within a few days took well over a year to transmit. It was only in late October 2016 that Earth finished receiving the stored data. In April 2017, after being "awake" since late 2014, the New Horizons probe went into hibernation for several months as it moved through deep space. Other than routine course corrections and instrument tests, the spacecraft spent most of its time in hibernation over the following year.

The end of this hibernation came in June 2018, when the spacecraft "awoke" once again. With its systems functioning normally, the time had come to prepare for its flyby of 2014 MU69, which was now less than 150 million miles away (a comparatively small distance compared to the 3.8 billion that the spacecraft had already traveled). This object had been nicknamed "Ultima Thule" a few months earlier, referring to a classical term for a place beyond the borders of the known world. Kuiper Belt objects such as Ultimate Thule have remained nearly unchanged since the formation of the solar system. On December 2, New Horizons underwent a small course correction at a unprecedented distance of over four billion miles from Earth. The flyby program began December 26.

At 12:33am EST on January 1, 2019, New Horizons made its closest approach to Ultima Thule (2014 MU69) at a distance of 2,200 miles (3,500 km) from its surface. This was a much closer approach than to the Pluto system, partially because Ultima Thule is a much smaller body, but it did make the risk of encountering orbiting debris somewhat higher. The flyby itself was at a distance from Earth of about 4.1 billion miles (6.6 billion km), making it the most distant flyby ever. A few hours after, the probe took a small break from its outbound science objectives to transmit a telemetry signal to Earth and confirm success. However, New Horizons was so far from Earth that the signal took over 6 hours, even at the speed of light, to reach the satellite dishes of the Deep Space Network (DSN) at 10:30am EST.

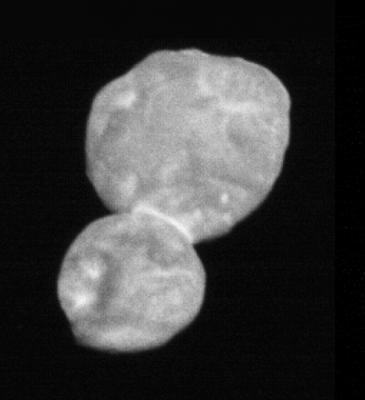

After the science mission was concluded, the long process of transmitting data back to Earth began. As in the Pluto encounter, this was a process that lasted more than a year. The first images returned (such as the one below) were low-resolution, but revealed Ultima Thule to be a conglomeration of two objects stuck together!

The above image is black and white, but Ultima Thule is in fact a reddish color. The larger and smaller lobes of the minor planet were nicknamed "Ultima" and "Thule" respectively, with the whole object being about 21 miles across at its largest extent.

NASA scientists speculated that Ultima Thule was formed through an accretionary process, illustrated above. A "cloud" of small objects at the beginning of the solar system gradually coalesced into two objects, which over great spans of millions of years gradually shed angular momentum until they eventually touched. New Horizons found that the binary object rotates with a period of 15 hours today.

The above image of Ultima Thule appeared on the cover of Science magazine and is a composite of the highest quality black-and-white photos obtained by New Horizons and data about color collected by other instruments.

In November 2019, Ultima Thule received the official name Arrokoth, meaning “sky” in the Powhatan/Algonquian language.

Having completed its flyby missions, New Horizons joined Pioneer 10 and 11 and Voyager 1 and 2 as the fifth probe to begin a journey outside the Solar System. The "edge" of the Solar System has no precise definition, but is generally associated with the region in which the solar wind (the stream of charged particles from the Sun) is slowed to a standstill by interaction with particles of the interstellar medium. New Horions' measurements of solar wind speed indicated that it was slowing down more rapidly than previous probes had measured. This revealed that the Solar System "edge" moves several AU in or out depending on how active the Sun is at a given time.

Sources: http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/