Storm Active: December 4-7

*This subtropical storm received no name despite being counted among the total of storms in the 2013 season. This is because though the low pressure system was monitored for development during its period of activity, analysis at the time did not indicate that it had become a subtropical cyclone. In February 2014, this storm was added to the 2013 season during the usual postseason analysis.

This system originated from an extratropical low pressure system formed which formed over the eastern Atlantic on December 3. Though the disturbance was already producing strong winds, there was not significant convection associated with it at the time. After completing a small counterclockwise loop well south of the Azores Islands, the low began to move northward and thunderstorm activity became more concentrated about the center of circulation. It was late in the evening on December 4 when the low was estimated to have developed into a subtropical storm. The cyclone had its peak intensity as a subtropical storm immediately after formation, with wind speeds of 50 mph and a central pressure of 997 mb.

Initially, the cyclone had a nested convective structure in that it had an area of central convection surrounded by a void of dry air around which there were a few outer bands. After persisting for about a day, this structure resolved into more traditional banding on December 6. By this time, the storm had begun to accelerate north-northwestward, approaching the Azores from the south. Wind shear also increased out of the west, and the subtropical storm began to weaken as it moved into cooler water. The unnamed storm lost subtropical characteristics very early on December 7, and dissipated shortly thereafter, bringing only showers and gusty winds to the Azores.

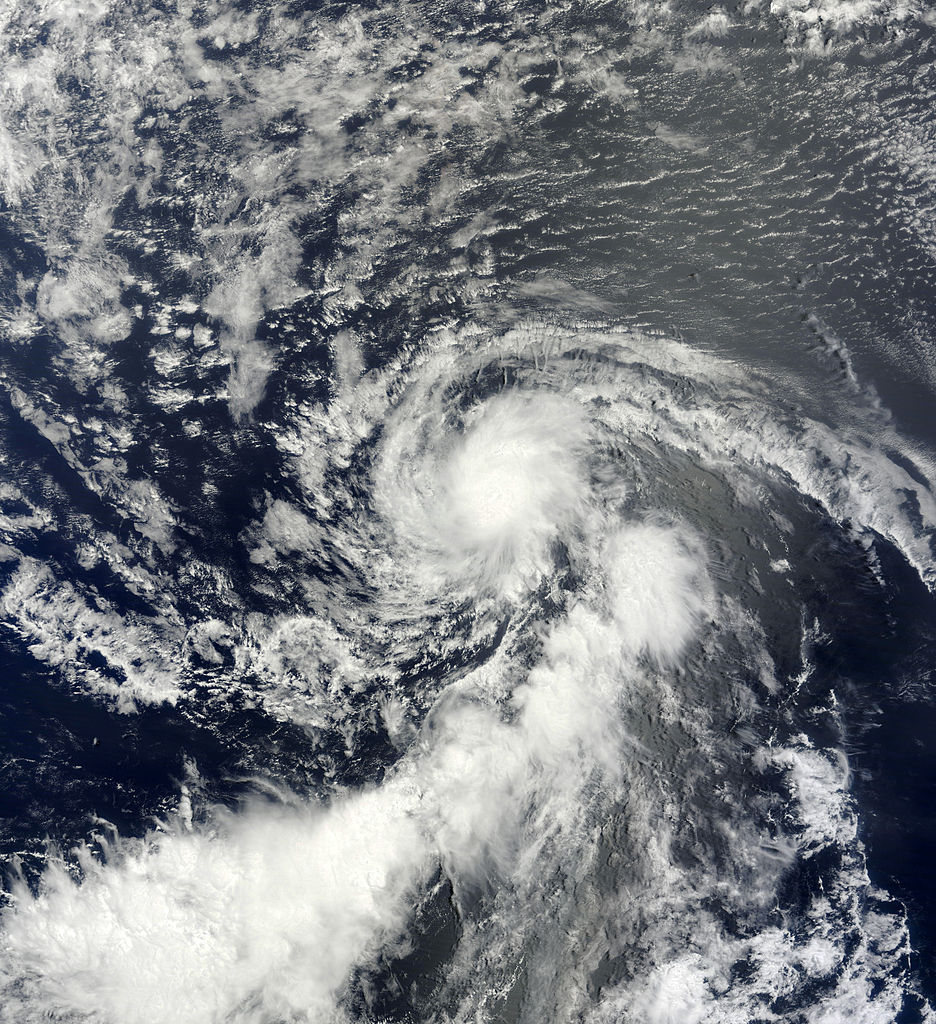

The above image illustrates the nested convective structure of the unnamed storm shortly after its formation.

The unnamed subtropical storm existed only in the far eastern Atlantic. It was one of only 15 December tropical cyclones in the Atlantic on record through 2013 and the first since 2007.

Showing posts with label 2013 Storms. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 2013 Storms. Show all posts

Friday, March 14, 2014

Tuesday, November 19, 2013

Tropical Storm Melissa (2013)

Storm Active: November 18-22

On November 12, a very strong cold front swept southeastward over the eastern half of the United States, bringing cold air in its wake as it departed the coast. A few days later, the large frontal boundary became stationary over the central Atlantic. By November 16, a broad area of low pressure was forming along the southern edge of the front, which at that time lay well northeast of Puerto Rico. The low had become better defined and produced winds of gale force on November 17. Meanwhile, the system was moving north-northwestward and developing more concentrated convection. By November 18, the low was deepening rapidly and a prominent banding feature beginning in the western side of the circulation and wrapping clockwise to its southeastern edge appeared. The frontal boundary that had been associated with the low was gone by that afternoon, so the system was designated Subtropical Storm Melissa.

Melissa was subtropical due to its broad wind field and circulation, but it was already a strong cyclone, and strengthened steadily into the morning of November 19 as it moved northwestward. During the afternoon, a cold front approaching from the west caused the cyclone to turn northeastward and begin to accelerate as Melissa reached its peak intensity as a subtropical storm of 65 mph winds and a pressure of 982 mb. Though convection became a little closer to the center of Melissa that evening, the outflow of the system had grown less impressive, and the maximum winds diminished through the early morning of November 20.

Later that morning, however, better defined curved bands developed, and enough convection appeared near the center that it was clear that the system had made the transition to Tropical Storm Melissa. Over the next day, the cyclone continued to move quickly to the northeast and then east-northeast into cooler water, but still managed to maintain tropical cyclone status into November 21. That afternoon, Melissa's peak winds actually increased to 65 mph once again, with a pressure of 980 mb. Since the system was over very cold water at the time, the strengthening indicated that Melissa would very soon be post-tropical. In fact, the remaining banding features continued to deteriorate that evening, and Melissa became post-tropical.

By this time, the cyclone had passed just north of the Azores. The outer wind field of the system caused gusty winds in the islands, but the diminishing convection was such that no significant rainfall occurred. The system that had been Melissa continued roughly eastward until its dissipation.

The above image shows Melissa as a subtropical storm on November 19. At this time, the center was still mainly devoid of convection, a common feature of subtropical storms.

Melissa did not significantly affect any land mass during its lifetime.

On November 12, a very strong cold front swept southeastward over the eastern half of the United States, bringing cold air in its wake as it departed the coast. A few days later, the large frontal boundary became stationary over the central Atlantic. By November 16, a broad area of low pressure was forming along the southern edge of the front, which at that time lay well northeast of Puerto Rico. The low had become better defined and produced winds of gale force on November 17. Meanwhile, the system was moving north-northwestward and developing more concentrated convection. By November 18, the low was deepening rapidly and a prominent banding feature beginning in the western side of the circulation and wrapping clockwise to its southeastern edge appeared. The frontal boundary that had been associated with the low was gone by that afternoon, so the system was designated Subtropical Storm Melissa.

Melissa was subtropical due to its broad wind field and circulation, but it was already a strong cyclone, and strengthened steadily into the morning of November 19 as it moved northwestward. During the afternoon, a cold front approaching from the west caused the cyclone to turn northeastward and begin to accelerate as Melissa reached its peak intensity as a subtropical storm of 65 mph winds and a pressure of 982 mb. Though convection became a little closer to the center of Melissa that evening, the outflow of the system had grown less impressive, and the maximum winds diminished through the early morning of November 20.

Later that morning, however, better defined curved bands developed, and enough convection appeared near the center that it was clear that the system had made the transition to Tropical Storm Melissa. Over the next day, the cyclone continued to move quickly to the northeast and then east-northeast into cooler water, but still managed to maintain tropical cyclone status into November 21. That afternoon, Melissa's peak winds actually increased to 65 mph once again, with a pressure of 980 mb. Since the system was over very cold water at the time, the strengthening indicated that Melissa would very soon be post-tropical. In fact, the remaining banding features continued to deteriorate that evening, and Melissa became post-tropical.

By this time, the cyclone had passed just north of the Azores. The outer wind field of the system caused gusty winds in the islands, but the diminishing convection was such that no significant rainfall occurred. The system that had been Melissa continued roughly eastward until its dissipation.

The above image shows Melissa as a subtropical storm on November 19. At this time, the center was still mainly devoid of convection, a common feature of subtropical storms.

Melissa did not significantly affect any land mass during its lifetime.

Labels:

2013 Storms

Tuesday, October 22, 2013

Tropical Storm Lorenzo (2013)

Storm Active: October 21-24

On October 20, a low pressure center formed along a trough over the central Atlantic ocean and thunderstorms began to concentrate about it. By the next day, a surface circulation was developing, and the system was designated Tropical Depression Thirteen that evening. The cyclone was already moving northeastward at the time of formation, and continued to move out into the open waters of the Atlantic.

Overnight and into the morning of October 22, Thirteen became more organized as convection continued to increase in the relatively friendly atmospheric environment. Soon, the cyclone had developed a symmetric dense overcast, and thus strengthened into Tropical Storm Lorenzo. The storm's organization increased further that morning, bringing Lorenzo to its peak intensity of 50 mph winds and a pressure of 1003 mb. By this time, the system was moving toward the east, having navigated around the upper edge of a mid-level ridge.

Lorenzo maintained its intensity until October 23, when shear increased substantially out of the northwest and decoupled the surface and mid-level circulations of the system and displaced convection from the cyclone's eastern side. Before long, all thunderstorm activity had been obliterated by the blast of wind shear, and Lorenzo was downgraded to a tropical depression that night. During the morning of October 24, the system degenerated into a remnant low. The low dissipated a few days later.

The above image shows Lorenzo near its peak intensity.

Lorenzo was a short-lived tropical storm, and did not affect land.

On October 20, a low pressure center formed along a trough over the central Atlantic ocean and thunderstorms began to concentrate about it. By the next day, a surface circulation was developing, and the system was designated Tropical Depression Thirteen that evening. The cyclone was already moving northeastward at the time of formation, and continued to move out into the open waters of the Atlantic.

Overnight and into the morning of October 22, Thirteen became more organized as convection continued to increase in the relatively friendly atmospheric environment. Soon, the cyclone had developed a symmetric dense overcast, and thus strengthened into Tropical Storm Lorenzo. The storm's organization increased further that morning, bringing Lorenzo to its peak intensity of 50 mph winds and a pressure of 1003 mb. By this time, the system was moving toward the east, having navigated around the upper edge of a mid-level ridge.

Lorenzo maintained its intensity until October 23, when shear increased substantially out of the northwest and decoupled the surface and mid-level circulations of the system and displaced convection from the cyclone's eastern side. Before long, all thunderstorm activity had been obliterated by the blast of wind shear, and Lorenzo was downgraded to a tropical depression that night. During the morning of October 24, the system degenerated into a remnant low. The low dissipated a few days later.

The above image shows Lorenzo near its peak intensity.

Lorenzo was a short-lived tropical storm, and did not affect land.

Labels:

2013 Storms

Friday, October 4, 2013

Tropical Storm Karen (2013)

Storm Active: October 3-6

On September 28, a tropical disturbance formed in the southern Caribbean sea, and began to track slowly northwestward. Over the next couple of days, the trough associated with the disturbance became much better defined, but the convection associated with the system remained disorganized. Convection increased markedly around the deepening low pressure center during the days of October 1 and 2 as the system approached the Gulf of Mexico, but aircraft investigation did not discover a well-defined center of circulation. The system caused very heavy rainfall and gusty winds in eastern Cuba as it passed by, and on October 3, as the system entered the southeastern Gulf of Mexico, a defined center appeared. The system was upgraded to Tropical Storm Karen. Due to the exceptionally high winds found east of the center, the initial intensity of the cyclone was already 60 mph!

Though by the measured wind speeds, Karen was a strong tropical storm, it did not appear as such. Strong upper-level winds constantly exposed the center overnight and into October 4 as the storm moved into the central Gulf. Over the next day, Karen continued to struggle north-northwestward, weakening gradually as wind shear displaced thunderstorm activity to the east of the center. By the morning of October 5, the system had become a minimal tropical storm and was approaching the Gulf Coast.

Later that day, Karen paused again, becoming nearly stationary south of the Louisiana coastline due to a ridge situated to its east. Atmospheric conditions continued to worsen that evening, and it became evident that the cyclone's circulation was slowly deteriorating. It was downgraded to a tropical depression overnight, and dissipated early on September 6, never having made landfall. Some of the moisture associated with Karen moved northward along a frontal boundary over the next day and caused enhanced rainfall up and down the east coast.

Even at peak intensity, when the cyclone was producing 65 mph winds, Karen did not exhibit much convective organization.

Probably due to its shallow circulation, Karen's forward motion diminished as it entered the northern Gulf of Mexico and the system was ripped apart by wind shear.

On September 28, a tropical disturbance formed in the southern Caribbean sea, and began to track slowly northwestward. Over the next couple of days, the trough associated with the disturbance became much better defined, but the convection associated with the system remained disorganized. Convection increased markedly around the deepening low pressure center during the days of October 1 and 2 as the system approached the Gulf of Mexico, but aircraft investigation did not discover a well-defined center of circulation. The system caused very heavy rainfall and gusty winds in eastern Cuba as it passed by, and on October 3, as the system entered the southeastern Gulf of Mexico, a defined center appeared. The system was upgraded to Tropical Storm Karen. Due to the exceptionally high winds found east of the center, the initial intensity of the cyclone was already 60 mph!

Though by the measured wind speeds, Karen was a strong tropical storm, it did not appear as such. Strong upper-level winds constantly exposed the center overnight and into October 4 as the storm moved into the central Gulf. Over the next day, Karen continued to struggle north-northwestward, weakening gradually as wind shear displaced thunderstorm activity to the east of the center. By the morning of October 5, the system had become a minimal tropical storm and was approaching the Gulf Coast.

Later that day, Karen paused again, becoming nearly stationary south of the Louisiana coastline due to a ridge situated to its east. Atmospheric conditions continued to worsen that evening, and it became evident that the cyclone's circulation was slowly deteriorating. It was downgraded to a tropical depression overnight, and dissipated early on September 6, never having made landfall. Some of the moisture associated with Karen moved northward along a frontal boundary over the next day and caused enhanced rainfall up and down the east coast.

Even at peak intensity, when the cyclone was producing 65 mph winds, Karen did not exhibit much convective organization.

Probably due to its shallow circulation, Karen's forward motion diminished as it entered the northern Gulf of Mexico and the system was ripped apart by wind shear.

Labels:

2013 Storms

Sunday, September 29, 2013

Tropical Storm Jerry (2013)

Storm Active: September 28-October 3

On September 26, a large area of disturbed weather formed over the central Atlantic ocean in association with a surface trough and an upper-level low. The system moved generally northwestward over the next couple of days, and despite fairly strong upper-level winds, thunderstorm activity began to concentrate around a forming low pressure center on September 27. During the next day, convection remained displaced to the north or northeast of the center of circulation, even though gale force wind gusts appeared to be occurring, and so the system was not yet tropical, but a slight increase in organization late on September 28 indicated the formation of Tropical Depression Eleven.

At the time of formation, the depression was skirting around the northern periphery of a subtropical ridge, and it turned northeast by early on September 29. The center continued to be alternately exposed and covered by a temporary canopy of convection throughout that day due to continuing shear, so the system's depression status was maintained. Overnight, a stronger burst of thunderstorm activity appeared, though it still remained largely in the eastern half of the circulation. However, slow development continued, and by by late morning on September 30, the system was upgraded to Tropical Storm Jerry.

The banding features of the circulation also improved that night, and the maximum winds of Jerry increased. However, the increase in organization was short-lived, as the convective structure deteriorated significantly early on October 1, and the storm weakened again. An upper-level low above the system continually bashed it with dry air, contributing to the weakening. By this time, the development of another ridge to Jerry's north left the cyclone in very weak steering currents, and so the storm was nearly stationary. Over the next day, the storm changed very little, and moved very little; even by the morning of October 2 it had only begun to drift back westward.

Finally, a trough moving moving northeastward picked up Jerry later that day, and began to accelerate the system northeastward. By this time, Jerry displayed deep convection so intermittently that it had to be downgraded to a tropical depression that night. On October 3, the system fell below the organization threshold of a tropical cyclone, and was downgraded to a remnant low. Over the next several days, the remnants continued northeastward and interacted with a trough of low pressure, the combination eventually bringing some rainfall to the Azores Islands.

Jerry experienced strong wind shear throughout its lifetime.

Tropical Storm Jerry remained nearly stationary for about a day around October 2 when it was embedded in weak steering currents.

On September 26, a large area of disturbed weather formed over the central Atlantic ocean in association with a surface trough and an upper-level low. The system moved generally northwestward over the next couple of days, and despite fairly strong upper-level winds, thunderstorm activity began to concentrate around a forming low pressure center on September 27. During the next day, convection remained displaced to the north or northeast of the center of circulation, even though gale force wind gusts appeared to be occurring, and so the system was not yet tropical, but a slight increase in organization late on September 28 indicated the formation of Tropical Depression Eleven.

At the time of formation, the depression was skirting around the northern periphery of a subtropical ridge, and it turned northeast by early on September 29. The center continued to be alternately exposed and covered by a temporary canopy of convection throughout that day due to continuing shear, so the system's depression status was maintained. Overnight, a stronger burst of thunderstorm activity appeared, though it still remained largely in the eastern half of the circulation. However, slow development continued, and by by late morning on September 30, the system was upgraded to Tropical Storm Jerry.

The banding features of the circulation also improved that night, and the maximum winds of Jerry increased. However, the increase in organization was short-lived, as the convective structure deteriorated significantly early on October 1, and the storm weakened again. An upper-level low above the system continually bashed it with dry air, contributing to the weakening. By this time, the development of another ridge to Jerry's north left the cyclone in very weak steering currents, and so the storm was nearly stationary. Over the next day, the storm changed very little, and moved very little; even by the morning of October 2 it had only begun to drift back westward.

Finally, a trough moving moving northeastward picked up Jerry later that day, and began to accelerate the system northeastward. By this time, Jerry displayed deep convection so intermittently that it had to be downgraded to a tropical depression that night. On October 3, the system fell below the organization threshold of a tropical cyclone, and was downgraded to a remnant low. Over the next several days, the remnants continued northeastward and interacted with a trough of low pressure, the combination eventually bringing some rainfall to the Azores Islands.

Jerry experienced strong wind shear throughout its lifetime.

Tropical Storm Jerry remained nearly stationary for about a day around October 2 when it was embedded in weak steering currents.

Labels:

2013 Storms

Friday, September 13, 2013

Hurricane Ingrid (2013)

Storm Active: September 12-17

On September 10, a disturbance located just east of the Yucatan Peninsula began to show signs of development. Like several systems before it, the disturbance did not organize further until it passed over the peninsula and entered the Bay of Campeche. This occurred early on September 12, at which time thunderstorm activity began to concentrate near a low-pressure center. Organization continued to increase during the afternoon, and advisories were initiated on Tropical Depression Ten early that evening.

Any significant forward speed that Ten initially had toward the west evaporated overnight, as light steering currents caused the cyclone to become nearly stationary over the extreme southwestern Bay of Campeche. On September 13, the system gained some organization as its central pressure decreased, and it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Ingrid. A ridge to Ingrid's north continued to keep it nearly stationary that day, though the cyclone drifted slightly to the west, coming very close to the coast of Mexico that afternoon. Meanwhile, a tropical system formed in the Pacific Ocean just off of southwestern Mexico in the center of a large area of disturbed weather. Though this system caused some wind shear on Ingrid, its main effect was to produce an extremely vast area of showers and thunderstorms stretching from the Bay of Campeche, over Mexico, and into the Pacific Ocean. This phenomenon, coupled with Ingrid being nearly stationary, caused immense amounts of rainfall across much of southern Mexico.

During that evening, Ingrid began to reverse direction and move roughly north-northeast as the ridge lifted out of Texas. Meanwhile, a Central Dense Overcast (CDO) appeared in association with Ingrid and banding improved, suggesting that the storm was strengthening rapidly. Thus a special advisory was issued by the National Hurricane Center bringing the cyclone's intensity to 60 mph winds. Gradual intensification continued through September 14, and with the hint of an eye appearing on visual satellite imagery that afternoon, Ingrid was upgraded to a category 1 hurricane. Though moderate shear associated with Tropical Storm Manuel in the East Pacific continued to cause shear, Ingrid remained resilient: the eye disappeared, but an eyewall of very strong convection that appeared overnight indicated that the hurricane had continued to strengthen into September 15. The cyclone had begun to turn northwest that morning as well, due to the influence of a forming ridge to its northeast.

Upper-level winds still affected the system, however, and later that day they displaced the most powerful thunderstorms to the eastern hemisphere of the circulation, leaving the center nearly exposed on the western side. Due to this loss of organization, Ingrid weakened slightly, but was still a minimal hurricane, producing some hurricane force winds east of the center. This status quo remained unchanged as the cyclone approached the coast of Mexico overnight and during the morning of September 16. Later that morning, Ingrid made landfall in Mexico and, at about the same time, weakened to a tropical storm. Over the next day, though the system continued to produce deep convection and heavy rain, the circulation itself was ripped apart by the mountainous terrain. By early on September 17, Ingrid had dissipated.

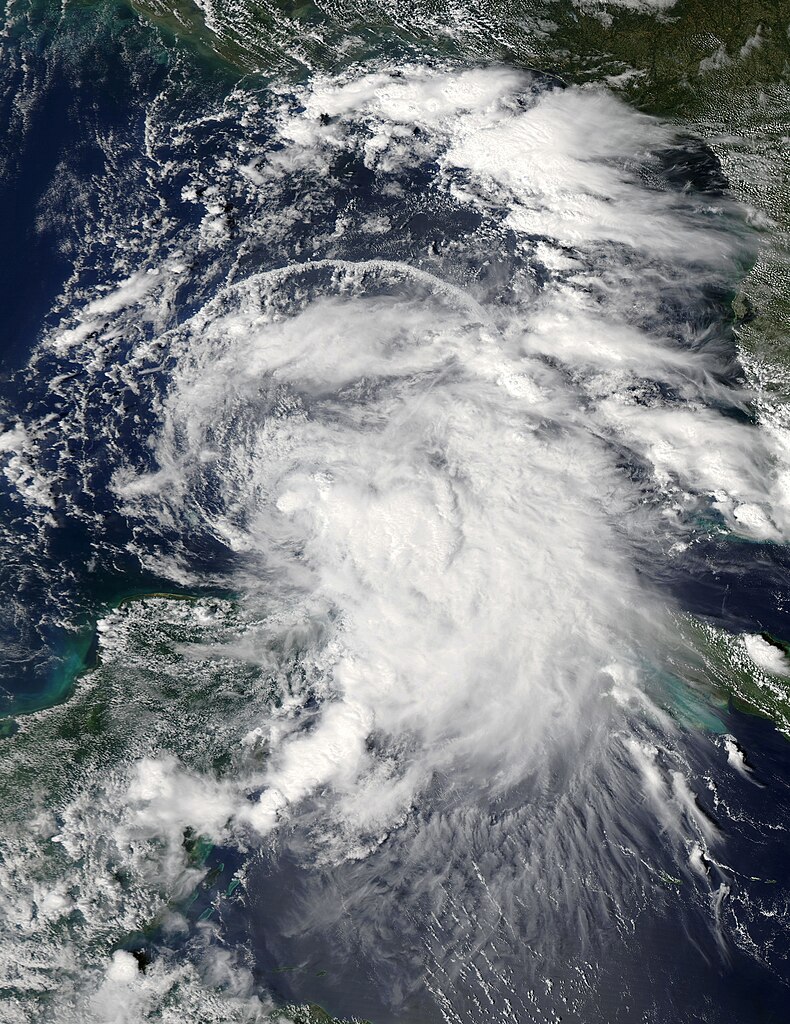

Ingrid did not have the appearance of a traditional hurricane, even near peak intensity, as above: the cyclone still appears lopsided and the convection was often displaced to the east of the center.

Ingrid was a meandering and slow-moving storm. As a result, its main effect was prolonged heavy rainfall over some areas of Mexico, which caused severe flooding.

On September 10, a disturbance located just east of the Yucatan Peninsula began to show signs of development. Like several systems before it, the disturbance did not organize further until it passed over the peninsula and entered the Bay of Campeche. This occurred early on September 12, at which time thunderstorm activity began to concentrate near a low-pressure center. Organization continued to increase during the afternoon, and advisories were initiated on Tropical Depression Ten early that evening.

Any significant forward speed that Ten initially had toward the west evaporated overnight, as light steering currents caused the cyclone to become nearly stationary over the extreme southwestern Bay of Campeche. On September 13, the system gained some organization as its central pressure decreased, and it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Ingrid. A ridge to Ingrid's north continued to keep it nearly stationary that day, though the cyclone drifted slightly to the west, coming very close to the coast of Mexico that afternoon. Meanwhile, a tropical system formed in the Pacific Ocean just off of southwestern Mexico in the center of a large area of disturbed weather. Though this system caused some wind shear on Ingrid, its main effect was to produce an extremely vast area of showers and thunderstorms stretching from the Bay of Campeche, over Mexico, and into the Pacific Ocean. This phenomenon, coupled with Ingrid being nearly stationary, caused immense amounts of rainfall across much of southern Mexico.

During that evening, Ingrid began to reverse direction and move roughly north-northeast as the ridge lifted out of Texas. Meanwhile, a Central Dense Overcast (CDO) appeared in association with Ingrid and banding improved, suggesting that the storm was strengthening rapidly. Thus a special advisory was issued by the National Hurricane Center bringing the cyclone's intensity to 60 mph winds. Gradual intensification continued through September 14, and with the hint of an eye appearing on visual satellite imagery that afternoon, Ingrid was upgraded to a category 1 hurricane. Though moderate shear associated with Tropical Storm Manuel in the East Pacific continued to cause shear, Ingrid remained resilient: the eye disappeared, but an eyewall of very strong convection that appeared overnight indicated that the hurricane had continued to strengthen into September 15. The cyclone had begun to turn northwest that morning as well, due to the influence of a forming ridge to its northeast.

Upper-level winds still affected the system, however, and later that day they displaced the most powerful thunderstorms to the eastern hemisphere of the circulation, leaving the center nearly exposed on the western side. Due to this loss of organization, Ingrid weakened slightly, but was still a minimal hurricane, producing some hurricane force winds east of the center. This status quo remained unchanged as the cyclone approached the coast of Mexico overnight and during the morning of September 16. Later that morning, Ingrid made landfall in Mexico and, at about the same time, weakened to a tropical storm. Over the next day, though the system continued to produce deep convection and heavy rain, the circulation itself was ripped apart by the mountainous terrain. By early on September 17, Ingrid had dissipated.

Ingrid did not have the appearance of a traditional hurricane, even near peak intensity, as above: the cyclone still appears lopsided and the convection was often displaced to the east of the center.

Ingrid was a meandering and slow-moving storm. As a result, its main effect was prolonged heavy rainfall over some areas of Mexico, which caused severe flooding.

Labels:

2013 Storms

Monday, September 9, 2013

Hurricane Humberto (2013)

Storm Active: September 8-14, 16-19

On September 6, a tropical wave over western Africa approached the coastline and began to show signs of development. By the next day, the wave already had a well-defined circulation even as the system still interacted with the African landmass. Thunderstorms rapidly concentrated near the low-pressure center and the system moved westward, and by the afternoon of September 8, very deep convection had appeared just west of the low-level center, and the system was organized enough to be classified Tropical Depression Nine.

In a region of light shear and warm water, Nine began to strengthen immediately, becoming Tropical Storm Humberto early on September 9. During the day, heavy rain and tropical storm force winds began to spread into the southern Cape Verde Islands as the system passed to the south. As Humberto moved away from the islands later that day, shear plummeted further, and banding features improved significantly, suggesting that the storm was undergoing strengthening. The intensification continued steadily into September 10, by which time a weakness in the ridge to Humberto's north was causing it to gradually turn northward.

The dry air attempted to invade the system that afternoon, causing the cloud tops to warm near the center, but the structure of the cyclone continued to improve, bringing it to near hurricane strength. Thus, when deep convection recovered and again wrapped around the circulation early on September 11, Humberto had achieved enough organization to be upgraded to a hurricane, and became the first hurricane of the 2013 season.

By that afternoon, the hurricane was moving almost due northward, and was already traveling into cooler waters. However, outflow and banding improved further, and hints of an eye and dense eyewall appeared, suggesting that Humberto had reached its peak intensity of 85 mph winds and a pressure of 982 mb by early on September 12. By this time, Humberto had become a large hurricane and was still expanding, with tropical storm force winds extending up to 170 miles from the center by that afternoon.

But more hostile conditions were beginning to take their toll on Humberto. Driven by stronger shear out of the west-southwest, dry and stable air began to invade the circulation that day, pushing deep convection to the northeastern quadrant of the circulation and weakening the cyclone to a minimal hurricane by early on September 13.

The weakening did not stop there. Later on September 13, Humberto lost all convection whatsoever, and diminished rapidly into a weak tropical storm. Though the circulation itself remained impressive, nearly all cloud cover was lost by September 14. Meanwhile, the rebuilding of the ridge to the north of the system had caused Humberto to turn back to the west. Since by later that day, the system had been without convection near the center for 24 hours, as per standard practice it was downgraded to a remnant low.

Despite the downgrade, the post-tropical cyclone began to gain organization back almost immediately as it moved into warmer waters and more friendly atmospheric conditions. By September 15, a large area of convection had reappeared northeast of the center, but upper-level winds were still too strong for it to wrap around the circulation center. However, on September 16, post-tropical cyclone Humberto gained just enough thunderstorm activity appeared near the center for advisories to be re-initiated. Over the next 18 hours, the newly reformed system had no consistent forward motion, as it was interacting with a mid- to upper-level low. The same low was also still bringing strong shear over the system, causing convection near the center to periodically reform and dissipate, and causing Humberto to fluctuate in intensity, though still remaining a weak tropical storm.

The upper-level low that caused Humberto to meander also altered its structure. During the day on September 17, a large area devoid of convection appeared around the center of circulation, with rain bands enclosing it. Such structures are characteristic of subtropical storms, and this may have resulted from the temporary alignment of the surface low associated with Humberto and the upper-level low with which it interacted. The cyclone began to assume a more definite north-northwestward motion that evening. Convection still struggled to wrap around the center of the system through September 18, so the system was downgraded to a tropical depression that evening. The surface circulation lost definition further on September 19, and Humberto dissipated early that evening.

Humberto became the first hurricane of the 2013 Atlantic hurricane season on September 11, well out to sea. This was the second-latest formation of a hurricane in the satellite era, behind only 2002.

A break in the subtropical ridge in the northeast Atlantic caused Humberto to turn north anomalously far east. This prevented the cyclone from affecting any landmasses, with the exception of the Cape Verde Islands.

On September 6, a tropical wave over western Africa approached the coastline and began to show signs of development. By the next day, the wave already had a well-defined circulation even as the system still interacted with the African landmass. Thunderstorms rapidly concentrated near the low-pressure center and the system moved westward, and by the afternoon of September 8, very deep convection had appeared just west of the low-level center, and the system was organized enough to be classified Tropical Depression Nine.

In a region of light shear and warm water, Nine began to strengthen immediately, becoming Tropical Storm Humberto early on September 9. During the day, heavy rain and tropical storm force winds began to spread into the southern Cape Verde Islands as the system passed to the south. As Humberto moved away from the islands later that day, shear plummeted further, and banding features improved significantly, suggesting that the storm was undergoing strengthening. The intensification continued steadily into September 10, by which time a weakness in the ridge to Humberto's north was causing it to gradually turn northward.

The dry air attempted to invade the system that afternoon, causing the cloud tops to warm near the center, but the structure of the cyclone continued to improve, bringing it to near hurricane strength. Thus, when deep convection recovered and again wrapped around the circulation early on September 11, Humberto had achieved enough organization to be upgraded to a hurricane, and became the first hurricane of the 2013 season.

By that afternoon, the hurricane was moving almost due northward, and was already traveling into cooler waters. However, outflow and banding improved further, and hints of an eye and dense eyewall appeared, suggesting that Humberto had reached its peak intensity of 85 mph winds and a pressure of 982 mb by early on September 12. By this time, Humberto had become a large hurricane and was still expanding, with tropical storm force winds extending up to 170 miles from the center by that afternoon.

But more hostile conditions were beginning to take their toll on Humberto. Driven by stronger shear out of the west-southwest, dry and stable air began to invade the circulation that day, pushing deep convection to the northeastern quadrant of the circulation and weakening the cyclone to a minimal hurricane by early on September 13.

The weakening did not stop there. Later on September 13, Humberto lost all convection whatsoever, and diminished rapidly into a weak tropical storm. Though the circulation itself remained impressive, nearly all cloud cover was lost by September 14. Meanwhile, the rebuilding of the ridge to the north of the system had caused Humberto to turn back to the west. Since by later that day, the system had been without convection near the center for 24 hours, as per standard practice it was downgraded to a remnant low.

Despite the downgrade, the post-tropical cyclone began to gain organization back almost immediately as it moved into warmer waters and more friendly atmospheric conditions. By September 15, a large area of convection had reappeared northeast of the center, but upper-level winds were still too strong for it to wrap around the circulation center. However, on September 16, post-tropical cyclone Humberto gained just enough thunderstorm activity appeared near the center for advisories to be re-initiated. Over the next 18 hours, the newly reformed system had no consistent forward motion, as it was interacting with a mid- to upper-level low. The same low was also still bringing strong shear over the system, causing convection near the center to periodically reform and dissipate, and causing Humberto to fluctuate in intensity, though still remaining a weak tropical storm.

The upper-level low that caused Humberto to meander also altered its structure. During the day on September 17, a large area devoid of convection appeared around the center of circulation, with rain bands enclosing it. Such structures are characteristic of subtropical storms, and this may have resulted from the temporary alignment of the surface low associated with Humberto and the upper-level low with which it interacted. The cyclone began to assume a more definite north-northwestward motion that evening. Convection still struggled to wrap around the center of the system through September 18, so the system was downgraded to a tropical depression that evening. The surface circulation lost definition further on September 19, and Humberto dissipated early that evening.

Humberto became the first hurricane of the 2013 Atlantic hurricane season on September 11, well out to sea. This was the second-latest formation of a hurricane in the satellite era, behind only 2002.

A break in the subtropical ridge in the northeast Atlantic caused Humberto to turn north anomalously far east. This prevented the cyclone from affecting any landmasses, with the exception of the Cape Verde Islands.

Labels:

2013 Storms

Friday, September 6, 2013

Tropical Depression Eight (2013)

Storm Active: September 6-7

A tropical wave in the northwestern Caribbean Sea began to exhibit scattered shower activity on September 2. However, on September 3, the system moved over the Yucatan Peninsula, which temporarily stifled development. By September 5, the wave had reemerged into the Bay of Campeche and acquired a low pressure center, around which more concentrated convection appeared. By this time, the system had turned west-southwest towards Mexico, where land would quickly dissipate the system. However, the disturbance stalled just off the coast during the afternoon of September 6, giving it just enough time to develop sufficient organization and banding features to be classified as Tropical Depression Eight.

A few hours later, the depression made landfall in Mexico, bringing 3-5 inches of rain over a large swath of land over the next couple days. However, by early on September 7, Eight's circulation had lost definition to the point that it was downgraded to a remnant low. By late that day, the remnant low had dissipated over southern Mexico.

Tropical Depression Eight was a very short-lived system which attained tropical status just hours before landfall. The above image shows Eight mere minutes before landfall in Mexico.

Eight spent only 14.5 hours as a tropical cyclone.

A tropical wave in the northwestern Caribbean Sea began to exhibit scattered shower activity on September 2. However, on September 3, the system moved over the Yucatan Peninsula, which temporarily stifled development. By September 5, the wave had reemerged into the Bay of Campeche and acquired a low pressure center, around which more concentrated convection appeared. By this time, the system had turned west-southwest towards Mexico, where land would quickly dissipate the system. However, the disturbance stalled just off the coast during the afternoon of September 6, giving it just enough time to develop sufficient organization and banding features to be classified as Tropical Depression Eight.

A few hours later, the depression made landfall in Mexico, bringing 3-5 inches of rain over a large swath of land over the next couple days. However, by early on September 7, Eight's circulation had lost definition to the point that it was downgraded to a remnant low. By late that day, the remnant low had dissipated over southern Mexico.

Tropical Depression Eight was a very short-lived system which attained tropical status just hours before landfall. The above image shows Eight mere minutes before landfall in Mexico.

Eight spent only 14.5 hours as a tropical cyclone.

Labels:

2013 Storms

Thursday, September 5, 2013

Tropical Storm Gabrielle (2013)

Storm Active: September 4-5, 10-13

On August 26, a tropical wave formed near the coast of Africa and moved westward. Shower activity associated with the system remained minimal due to an unfavorable upper atmosphere for most of the next week. However, by August 31, a broad low pressure center had formed along the wave, and convection increased somewhat, though still remaining disorganized. On September 1, shower and thunderstorm activity associated with the disturbance spread over the islands forming the eastern edge of the Caribbean. Meanwhile, another tropical wave formed a few hundred miles east of the existing system, and the two systems began to interact, forming a widespread area of convective activity stretching from the eastern Caribbean well into the central Atlantic.

Wind shear declined significantly as the first low entered the Caribbean, but the system still struggled with a good deal of dry air aloft for the next few days as it remained nearly stationary in the far eastern Caribbean. On September 3, the low assumed a more northwesterly track, and more concentrated cloud cover appeared in the vicinity of the low pressure center, though the center itself remained poorly defined. However, on September 4, hurricane hunter aircraft investigating the system found a circulation organized enough to merit the low's classification as Tropical Depression Seven.

Partially due to the influence of the tropical wave still churning to its northeast, Seven continued to the northwest toward western Puerto Rico that evening. Small increases in outflow definition and a deepening of convection prompted the upgrade of Seven to Tropical Storm Gabrielle overnight. However, during the morning of September 6, it became clear that the surface circulation of Gabrielle had become decoupled from the mid-level atmospheric center by over 100 miles: the surface circulation was still approaching the channel between Puerto Rico and Hispaniola but the mid-level center and all the associated swirl in satellite imagery was displaced well to the northeast due to upper-level winds. This separation caused the system to quickly weaken into a tropical depression, and since a new surface low did not form in alignment with the structure of the upper-atmosphere, Gabrielle dissipated that evening. Heavy rains continued throughout the northeastern Caribbean due to the remnants of Gabrielle and still because of the lingering disturbance to the northeast over the next day.

The two systems finally combined as the remnants of Gabrielle moved north-northeastward, but the low-pressure center formerly associated with the tropical storm remained intact, and in fact moved into slightly more favorable conditions. On September 9, the low deepened and deep convection appeared near and to the east of its center. By early on September 10, the system had regenerated into Tropical Storm Gabrielle. Meanwhile, an upper-level low situated north of Bermuda altered the bearing of the tropical storm, pushing it in a more northerly direction toward Bermuda.

During that afternoon, Gabrielle became more organized despite experiencing shear out of the west and southwest, and quickly reached a peak intensity of 60 mph winds and a pressure of 1004 mb as it passed within 25 miles of Bermuda, bringing tropical storm force winds and heavy rainfall. However, shortly after Gabrielle reached this intensity, the southwesterly shear displaced the convection associated with the system to the east, exposing the center. This trend caused weakening into September 11. Meanwhile, the upper-level low north of Gabrielle had caused the cyclone to veer left further, and it was now bearing northwest at a slower forward speed. The circulation became almost totally void of convection that evening and Gabrielle weakened to a tropical depression but the cyclone recovered somewhat during the morning of September 12 as shear decreased.

This prompted the upgrade of the system back to a tropical storm that day. Gabrielle also began to accelerate northward and north-northeastward as it entered the flow of an approaching frontal system that evening. By early on September 13, the cyclone had once again weakened to a tropical depression as the associated convection lost its banding features and began to interact with an approaching front. Finally, later that day, the system lost its closed circulation and dissipated. The moisture from Gabrielle contributed to rainfall in Atlantic Canada the next day.

The above image shows Gabrielle shorting after reforming on September 10.

The track of Gabrielle took it very close to Bermuda at its peak intensity, causing some heavy rainfall and gusty winds.

On August 26, a tropical wave formed near the coast of Africa and moved westward. Shower activity associated with the system remained minimal due to an unfavorable upper atmosphere for most of the next week. However, by August 31, a broad low pressure center had formed along the wave, and convection increased somewhat, though still remaining disorganized. On September 1, shower and thunderstorm activity associated with the disturbance spread over the islands forming the eastern edge of the Caribbean. Meanwhile, another tropical wave formed a few hundred miles east of the existing system, and the two systems began to interact, forming a widespread area of convective activity stretching from the eastern Caribbean well into the central Atlantic.

Wind shear declined significantly as the first low entered the Caribbean, but the system still struggled with a good deal of dry air aloft for the next few days as it remained nearly stationary in the far eastern Caribbean. On September 3, the low assumed a more northwesterly track, and more concentrated cloud cover appeared in the vicinity of the low pressure center, though the center itself remained poorly defined. However, on September 4, hurricane hunter aircraft investigating the system found a circulation organized enough to merit the low's classification as Tropical Depression Seven.

Partially due to the influence of the tropical wave still churning to its northeast, Seven continued to the northwest toward western Puerto Rico that evening. Small increases in outflow definition and a deepening of convection prompted the upgrade of Seven to Tropical Storm Gabrielle overnight. However, during the morning of September 6, it became clear that the surface circulation of Gabrielle had become decoupled from the mid-level atmospheric center by over 100 miles: the surface circulation was still approaching the channel between Puerto Rico and Hispaniola but the mid-level center and all the associated swirl in satellite imagery was displaced well to the northeast due to upper-level winds. This separation caused the system to quickly weaken into a tropical depression, and since a new surface low did not form in alignment with the structure of the upper-atmosphere, Gabrielle dissipated that evening. Heavy rains continued throughout the northeastern Caribbean due to the remnants of Gabrielle and still because of the lingering disturbance to the northeast over the next day.

The two systems finally combined as the remnants of Gabrielle moved north-northeastward, but the low-pressure center formerly associated with the tropical storm remained intact, and in fact moved into slightly more favorable conditions. On September 9, the low deepened and deep convection appeared near and to the east of its center. By early on September 10, the system had regenerated into Tropical Storm Gabrielle. Meanwhile, an upper-level low situated north of Bermuda altered the bearing of the tropical storm, pushing it in a more northerly direction toward Bermuda.

During that afternoon, Gabrielle became more organized despite experiencing shear out of the west and southwest, and quickly reached a peak intensity of 60 mph winds and a pressure of 1004 mb as it passed within 25 miles of Bermuda, bringing tropical storm force winds and heavy rainfall. However, shortly after Gabrielle reached this intensity, the southwesterly shear displaced the convection associated with the system to the east, exposing the center. This trend caused weakening into September 11. Meanwhile, the upper-level low north of Gabrielle had caused the cyclone to veer left further, and it was now bearing northwest at a slower forward speed. The circulation became almost totally void of convection that evening and Gabrielle weakened to a tropical depression but the cyclone recovered somewhat during the morning of September 12 as shear decreased.

This prompted the upgrade of the system back to a tropical storm that day. Gabrielle also began to accelerate northward and north-northeastward as it entered the flow of an approaching frontal system that evening. By early on September 13, the cyclone had once again weakened to a tropical depression as the associated convection lost its banding features and began to interact with an approaching front. Finally, later that day, the system lost its closed circulation and dissipated. The moisture from Gabrielle contributed to rainfall in Atlantic Canada the next day.

The above image shows Gabrielle shorting after reforming on September 10.

The track of Gabrielle took it very close to Bermuda at its peak intensity, causing some heavy rainfall and gusty winds.

Labels:

2013 Storms

Monday, August 26, 2013

Tropical Storm Fernand (2013)

Storm Active: August 25-26

On August 23, thunderstorm activity increased markedly in association with a tropical wave situated over the western Caribbean sea, just east of the Yucatan Peninsula. Over the next day, the system brought significant rainfall to the peninsula and to other parts of Central America as it moved west-northwestward. Late on August 24, a low pressure center was identified along the tropical wave, and despite still being over land, the disturbance became more organized.

The low emerged into the Bay of Campeche on August 25, allowing the warm ocean water to fuel the development of convection near the center of circulation. By the afternoon, the convection had developed prominent banding features, meriting the upgrade of the disturbance into Tropical Depression Six. As the cyclone formed, it was already in a stage of rapid development, and aircraft data indicated that Six had strengthened into Tropical Storm Fernand just two hours after its initial designation. In addition, however, the same data suggested that the center had reformed farther south, and the track adjustment reduced Fernand's time over open water. Therefore, even as a concentrated inner core of very cold cloud tops developed, bringing Fernand to its peak intensity of 50 mph winds and a pressure of 1001 mb, the tropical storm swiftly made landfall in Mexico very early on August 26. By late that afternoon, Fernand had dissipated.

In the above image, Tropical Storm Fernand was in the midst of rapid development, though this process was quelled almost immediately by interaction with land.

Fernand was a very short-lived system, persisting as a tropical cyclone for little over a day.

On August 23, thunderstorm activity increased markedly in association with a tropical wave situated over the western Caribbean sea, just east of the Yucatan Peninsula. Over the next day, the system brought significant rainfall to the peninsula and to other parts of Central America as it moved west-northwestward. Late on August 24, a low pressure center was identified along the tropical wave, and despite still being over land, the disturbance became more organized.

The low emerged into the Bay of Campeche on August 25, allowing the warm ocean water to fuel the development of convection near the center of circulation. By the afternoon, the convection had developed prominent banding features, meriting the upgrade of the disturbance into Tropical Depression Six. As the cyclone formed, it was already in a stage of rapid development, and aircraft data indicated that Six had strengthened into Tropical Storm Fernand just two hours after its initial designation. In addition, however, the same data suggested that the center had reformed farther south, and the track adjustment reduced Fernand's time over open water. Therefore, even as a concentrated inner core of very cold cloud tops developed, bringing Fernand to its peak intensity of 50 mph winds and a pressure of 1001 mb, the tropical storm swiftly made landfall in Mexico very early on August 26. By late that afternoon, Fernand had dissipated.

In the above image, Tropical Storm Fernand was in the midst of rapid development, though this process was quelled almost immediately by interaction with land.

Fernand was a very short-lived system, persisting as a tropical cyclone for little over a day.

Labels:

2013 Storms

Thursday, August 15, 2013

Tropical Storm Erin (2013)

Storm Active: August 14-18

A strong tropical wave and associated low pressure system moved off of the African coast on August 13 and immediately began to organize. The next day, convection concentrated near the center as the system began to pass south of the Cape Verde Islands, bringing showers and some windy conditions. By the evening of August 14, the disturbance was sufficiently organized to be classified as Tropical Depression Five. At first, the highest winds were not situated over the center of circulation, but organization continued as the system tracked west-northwest, and by the morning of August 15, Five had strengthened into Tropical Storm Erin.

During that day, Erin was already struggling with the atmospheric dry air still present in that region of the Atlantic, fluctuating between periods of strong convection and nearly none at all. Meanwhile the cyclone turned slightly toward the northwest into a weakness in a ridge to its north, and entered a region of somewhat cooler waters. On August 16, wind shear out of the southwest increased also, driving convection off to the east of Erin's center, and the system was downgraded to a tropical depression. Late that night, however, a burst of convection reappeared, and satellite data suggested that Erin had restrengthened into a tropical storm.

Erin's new status was not to last, though, as the hostile conditions again tore away the cloud cover over the system's center of circulation on August 17. By that evening, the center also showed signs of elongation, and Erin was again downgraded to a tropical depression. The cyclone continued to degenerate on August 18, and became a remnant low that afternoon. The remnant low dissipated over the open Atlantic by August 20.

The image above shows Erin shortly after being named. The cyclone achieved only minimal tropical storm status.

A weakness in the subtropical ridge to its north allowed Erin to move northwestward into cooler water and very hostile atmospheric conditions. These conditions promptly dissipated the system.

A strong tropical wave and associated low pressure system moved off of the African coast on August 13 and immediately began to organize. The next day, convection concentrated near the center as the system began to pass south of the Cape Verde Islands, bringing showers and some windy conditions. By the evening of August 14, the disturbance was sufficiently organized to be classified as Tropical Depression Five. At first, the highest winds were not situated over the center of circulation, but organization continued as the system tracked west-northwest, and by the morning of August 15, Five had strengthened into Tropical Storm Erin.

During that day, Erin was already struggling with the atmospheric dry air still present in that region of the Atlantic, fluctuating between periods of strong convection and nearly none at all. Meanwhile the cyclone turned slightly toward the northwest into a weakness in a ridge to its north, and entered a region of somewhat cooler waters. On August 16, wind shear out of the southwest increased also, driving convection off to the east of Erin's center, and the system was downgraded to a tropical depression. Late that night, however, a burst of convection reappeared, and satellite data suggested that Erin had restrengthened into a tropical storm.

Erin's new status was not to last, though, as the hostile conditions again tore away the cloud cover over the system's center of circulation on August 17. By that evening, the center also showed signs of elongation, and Erin was again downgraded to a tropical depression. The cyclone continued to degenerate on August 18, and became a remnant low that afternoon. The remnant low dissipated over the open Atlantic by August 20.

The image above shows Erin shortly after being named. The cyclone achieved only minimal tropical storm status.

A weakness in the subtropical ridge to its north allowed Erin to move northwestward into cooler water and very hostile atmospheric conditions. These conditions promptly dissipated the system.

Labels:

2013 Storms

Thursday, July 25, 2013

Tropical Storm Dorian (2013)

Storm Active: July 24-27, August 3

On July 22, a tropical wave emerged off of the African coast centered around 12°N latitude. The wave was the strongest yet for the 2013 Atlantic hurricane season, and begin to organize almost immediately. By July 23, rotation was evident in the satellite presentation, and convection had become more concentrated about the newly-formed low pressure center. Later that day, the disturbance passed south of the Cape Verde Islands, bringing some scattered showers to the southernmost islands. The definition of the circulation improved further during the evening and thunderstorm activity persisted, so the low was upgraded to Tropical Depression Four early on July 24.

Later that morning, as the system moved west-northwest, it organized further, and strengthened into Tropical Storm Dorian. The storm was entering less favorable conditions, including the slightly cooler water of the central Atlantic and a large dry air mass to the northwest, but the effect of these factors was partially neutralized by a warm, moist air flow that continued into Dorian from the south. Over the next day, therefore, the tropical storm was still able to improve in outflow and convective organization, allowing it to intensify into a strong tropical storm by early on July 25.

Late that day, a large burst of convection flared up, and Dorian even exhibited a clouded eye briefly, reaching its peak intensity of 60 mph winds and a pressure of 999 mb. However, even though the system was now moving into warmer waters, it lost its equatorial inflow of moist air, and the circulation was largely at the mercy of the large dry air mass to its west. This dry air, coupled with moderate shear out of the southwest, disrupted the circulation during the evening of July 25, and Dorian became much less organized. The storm weakened into July 26, and meanwhile continued to race west-northwest, as a ridge to its north steered the shallower circulation faster than it had the previous day, when Dorian had been stronger.

Later that day, Dorian made a turn more toward the west and moved even faster. The circulation became totally exposed that evening as nearly all convection disappeared from the system. It was unclear whether Dorian was still a tropical system overnight, but some thunderstorm activity did redevelop during the early morning hours of July 27, prompting the National Hurricane Center to continue issuing advisories on the weak tropical storm. However, the wind shear had now increased to such a degree that it was eroding the circulation, and it became clear during the afternoon of the same day that Dorian's circulation was no longer closed and that it had degenerated into a tropical wave.

The remnants of Dorain continued west-northwestward and continued to produce gale force winds and convection. However, though a swirl in the clouds was evident, this was not due to a closed surface circulation, but to an upper-level low in association with the system. Thus, despite the fact that the disturbance was no longer a tropical cyclone, the north coasts of Puerto Rico and Hispaniola experienced high surf as the system continued to move west-northwestward. The moisture that had been part of Dorian began to spread over the Bahamas on July 31, and conditions improved as shear lessened. On August 1, more convection appeared and surface pressures fell near the western Bahamas during that day.

By August 2, a trough of low pressure was evident, but the system did not yet have a closed circulation. As the western edge of the system brushed Florida, the remnants of Dorian triggered showers and thunderstorms over various parts of the state. However, the low turned northward that day, navigating around the edge of the Bermuda High. Overnight, despite the fact that upper-level winds were again increasing, a closed circulation appeared, indicating that Dorian had reformed into a tropical depression. By the morning of August 3, convection was displaced well southwest of the center of circulation. But Dorian persisted after its reformation for only 12 hours, reaching only tropical depression intensity and degenerating into a remnant low by the afternoon. The low was absorbed by a frontal boundary the next day.

Dorian was afflicted by dry air for most of its lifetime. The above image shows the western half of the circulation to be partially exposed due to the same dry air, even though Dorian is near its peak intensity.

Before reforming on August 3, Dorian had for a time been only a tropical wave, with no associated low pressure center.

On July 22, a tropical wave emerged off of the African coast centered around 12°N latitude. The wave was the strongest yet for the 2013 Atlantic hurricane season, and begin to organize almost immediately. By July 23, rotation was evident in the satellite presentation, and convection had become more concentrated about the newly-formed low pressure center. Later that day, the disturbance passed south of the Cape Verde Islands, bringing some scattered showers to the southernmost islands. The definition of the circulation improved further during the evening and thunderstorm activity persisted, so the low was upgraded to Tropical Depression Four early on July 24.

Later that morning, as the system moved west-northwest, it organized further, and strengthened into Tropical Storm Dorian. The storm was entering less favorable conditions, including the slightly cooler water of the central Atlantic and a large dry air mass to the northwest, but the effect of these factors was partially neutralized by a warm, moist air flow that continued into Dorian from the south. Over the next day, therefore, the tropical storm was still able to improve in outflow and convective organization, allowing it to intensify into a strong tropical storm by early on July 25.

Late that day, a large burst of convection flared up, and Dorian even exhibited a clouded eye briefly, reaching its peak intensity of 60 mph winds and a pressure of 999 mb. However, even though the system was now moving into warmer waters, it lost its equatorial inflow of moist air, and the circulation was largely at the mercy of the large dry air mass to its west. This dry air, coupled with moderate shear out of the southwest, disrupted the circulation during the evening of July 25, and Dorian became much less organized. The storm weakened into July 26, and meanwhile continued to race west-northwest, as a ridge to its north steered the shallower circulation faster than it had the previous day, when Dorian had been stronger.

Later that day, Dorian made a turn more toward the west and moved even faster. The circulation became totally exposed that evening as nearly all convection disappeared from the system. It was unclear whether Dorian was still a tropical system overnight, but some thunderstorm activity did redevelop during the early morning hours of July 27, prompting the National Hurricane Center to continue issuing advisories on the weak tropical storm. However, the wind shear had now increased to such a degree that it was eroding the circulation, and it became clear during the afternoon of the same day that Dorian's circulation was no longer closed and that it had degenerated into a tropical wave.

The remnants of Dorain continued west-northwestward and continued to produce gale force winds and convection. However, though a swirl in the clouds was evident, this was not due to a closed surface circulation, but to an upper-level low in association with the system. Thus, despite the fact that the disturbance was no longer a tropical cyclone, the north coasts of Puerto Rico and Hispaniola experienced high surf as the system continued to move west-northwestward. The moisture that had been part of Dorian began to spread over the Bahamas on July 31, and conditions improved as shear lessened. On August 1, more convection appeared and surface pressures fell near the western Bahamas during that day.

By August 2, a trough of low pressure was evident, but the system did not yet have a closed circulation. As the western edge of the system brushed Florida, the remnants of Dorian triggered showers and thunderstorms over various parts of the state. However, the low turned northward that day, navigating around the edge of the Bermuda High. Overnight, despite the fact that upper-level winds were again increasing, a closed circulation appeared, indicating that Dorian had reformed into a tropical depression. By the morning of August 3, convection was displaced well southwest of the center of circulation. But Dorian persisted after its reformation for only 12 hours, reaching only tropical depression intensity and degenerating into a remnant low by the afternoon. The low was absorbed by a frontal boundary the next day.

Dorian was afflicted by dry air for most of its lifetime. The above image shows the western half of the circulation to be partially exposed due to the same dry air, even though Dorian is near its peak intensity.

Before reforming on August 3, Dorian had for a time been only a tropical wave, with no associated low pressure center.

Labels:

2013 Storms

Monday, July 8, 2013

Tropical Storm Chantal (2013)

Storm Active: July 7-10

During the first days of July, a tropical wave moved off of the coast of Africa and tracked rapidly westward. By July 5, concentrated thunderstorms had appeared in a association with a low pressure area at the southern tip of the tropical wave as it moved through the central Atlantic. Initially, development was not anticipated due to the timing: in early July, the central Atlantic does not often support tropical development, partially due to Saharan dry air dominating the region. However, the system remained exceptionally far south, between 5° and 10°N latitude, and it was isolated from the strong shear to its north.

On July 7, satellite data indicated the imminent development of a closed circulation in association with the wave as the low pressure system gained definition. Late that evening, the low was designated Tropical Storm Chantal, as it was observed to have tropical storm force winds. At the time, Chantal was tracking rapidly westward, at speeds in excess of 25 mph, embedded as it was in strong steering winds. During the day of July 8, Chantal's winds steadily increased and its circulation became better defined, but the convective organization remained quite ragged as strong subtropical ridges continued to steer the storm west to west-northwest.

On July 9, showers and thunderstorms began to impact the Windward Islands as the cyclone passed through. Bursts of thunderstorm activity flared up periodically throughout the day, and Chantal continued its trend of modest strengthening, managing to maintain its circulation despite its forward velocity. The system reached its peak intensity of 65 mph winds and a pressure of 1005 mb. However, that evening, increasing westerly shear finally began to take its toll, decoupling the tropical storm's circulation from the surrounding shower activity. By late that evening, nearly all convection had vanished, and the center was nearly impossible to identify.

While it appeared as though Chantal had lost its circulation entirely and degenerated into a tropical wave, rapid development of thunderstorm activity occurred during the morning of July 10 and a poorly defined circulation was found. The system also had made a turn back to the west, indicating a shallow circulation. Indeed, the pressure had risen and Chantal had weakened to a low-end tropical storm. However, heavy rain, mostly displaced to the north and east of the center, swept over much of Hispaniola that afternoon as the storm passed to the south. Finally, additional evidence emerged during the evening of the same day that the circulation had indeed disappeared, and advisories were discontinued as Chantal degenerated into a tropical wave.

A low pressure trough associated with the remnants of Chantal was still producing a large area of thunderstorms on July 11 as it drifted northwestward over eastern Cuba and into the Bahamas. Over the following two days, the disturbance continued to cause rainfall in the Bahamas, and eventually in parts of the U.S. southeast coast, but it did not show any signs of development, and on July 13 merged with a larger system to its north.

The above image shows Chantal, not at peak intensity, but perhaps at peak convective organization before it entered the Caribbean.

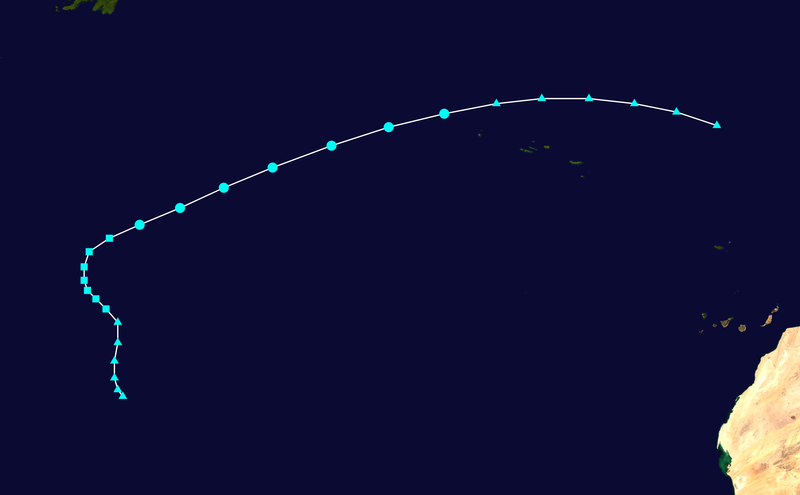

Chantal moved at a blistering pace before dissipating in the Caribbean. The final points on the track (triangles) show its progress as a disturbance over Hispaniola and Cuba, where it caused widespread flooding.

During the first days of July, a tropical wave moved off of the coast of Africa and tracked rapidly westward. By July 5, concentrated thunderstorms had appeared in a association with a low pressure area at the southern tip of the tropical wave as it moved through the central Atlantic. Initially, development was not anticipated due to the timing: in early July, the central Atlantic does not often support tropical development, partially due to Saharan dry air dominating the region. However, the system remained exceptionally far south, between 5° and 10°N latitude, and it was isolated from the strong shear to its north.

On July 7, satellite data indicated the imminent development of a closed circulation in association with the wave as the low pressure system gained definition. Late that evening, the low was designated Tropical Storm Chantal, as it was observed to have tropical storm force winds. At the time, Chantal was tracking rapidly westward, at speeds in excess of 25 mph, embedded as it was in strong steering winds. During the day of July 8, Chantal's winds steadily increased and its circulation became better defined, but the convective organization remained quite ragged as strong subtropical ridges continued to steer the storm west to west-northwest.

On July 9, showers and thunderstorms began to impact the Windward Islands as the cyclone passed through. Bursts of thunderstorm activity flared up periodically throughout the day, and Chantal continued its trend of modest strengthening, managing to maintain its circulation despite its forward velocity. The system reached its peak intensity of 65 mph winds and a pressure of 1005 mb. However, that evening, increasing westerly shear finally began to take its toll, decoupling the tropical storm's circulation from the surrounding shower activity. By late that evening, nearly all convection had vanished, and the center was nearly impossible to identify.

While it appeared as though Chantal had lost its circulation entirely and degenerated into a tropical wave, rapid development of thunderstorm activity occurred during the morning of July 10 and a poorly defined circulation was found. The system also had made a turn back to the west, indicating a shallow circulation. Indeed, the pressure had risen and Chantal had weakened to a low-end tropical storm. However, heavy rain, mostly displaced to the north and east of the center, swept over much of Hispaniola that afternoon as the storm passed to the south. Finally, additional evidence emerged during the evening of the same day that the circulation had indeed disappeared, and advisories were discontinued as Chantal degenerated into a tropical wave.

A low pressure trough associated with the remnants of Chantal was still producing a large area of thunderstorms on July 11 as it drifted northwestward over eastern Cuba and into the Bahamas. Over the following two days, the disturbance continued to cause rainfall in the Bahamas, and eventually in parts of the U.S. southeast coast, but it did not show any signs of development, and on July 13 merged with a larger system to its north.

The above image shows Chantal, not at peak intensity, but perhaps at peak convective organization before it entered the Caribbean.

Chantal moved at a blistering pace before dissipating in the Caribbean. The final points on the track (triangles) show its progress as a disturbance over Hispaniola and Cuba, where it caused widespread flooding.

Labels:

2013 Storms

Monday, June 17, 2013

Tropical Storm Barry (2013)

Storm Active: June 17-20

A tropical wave located off the eastern coast of Nicaragua began to show signs of organization on June 15. On June 16, a swirling of clouds became evident on satellite imagery, though a surface circulation had not yet formed and, in any case, the proximity of the developing circulation to central America limited thunderstorm activity.

However, the disturbance emerged into the northwest Caribbean on June 17, and late that morning, a low-level circulation appeared and the system was upgraded to Tropical Depression Two only 60 miles east of the coast of Belize. Later that day, the depression made landfall in Belize at an intensity of 35 mph winds and a pressure of 1008 mb, bringing heavy rainfall to the region.

The depression weakened over land, and lost definition, but the system continued to move west-northwest, and the northern half of the circulation regained convection as the northwestern portion emerged into the Bay of Campeche early on June 18. A ridge situated over the northern Gulf of Mexico weakened slightly that day, allowing the cyclone to shift north slightly in its path. As a result, the center entered the Bay of Campeche during the afternoon of that day, and thunderstorm activity soon recovered near the center.

Though moderate wind shear still affected the depression out of the southwest, the shear began to weaken during the morning of June 19, as the system made a turn westward toward the Mexican coast. This allowed the thunderstorm activity to increase markedly, and the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Barry that afternoon. The system continued to gain organization through the early morning of June 20, reaching its peak intensity of 45 mph winds and a pressure of 1003 mb before making its final landfall in Mexico later that morning.

The system quickly weakened over land, becoming a tropical depression that evening, and degenerating into a remnant low late that night. Barry main effect was heavy rainfall; the tropical storm dumped several inches of rain over a large swath of southern Mexico, with localized totals-especially in mountainous regions-exceeding 5 inches.

Tropical Storm Barry achieved its peak intensity as a weak tropical storm shortly before its second landfall in Mexico.

A combination of a slow forward speed and extensive moisture from the Bay of Campeche made Barry a significant flooding threat near the end of its life.

A tropical wave located off the eastern coast of Nicaragua began to show signs of organization on June 15. On June 16, a swirling of clouds became evident on satellite imagery, though a surface circulation had not yet formed and, in any case, the proximity of the developing circulation to central America limited thunderstorm activity.

However, the disturbance emerged into the northwest Caribbean on June 17, and late that morning, a low-level circulation appeared and the system was upgraded to Tropical Depression Two only 60 miles east of the coast of Belize. Later that day, the depression made landfall in Belize at an intensity of 35 mph winds and a pressure of 1008 mb, bringing heavy rainfall to the region.

The depression weakened over land, and lost definition, but the system continued to move west-northwest, and the northern half of the circulation regained convection as the northwestern portion emerged into the Bay of Campeche early on June 18. A ridge situated over the northern Gulf of Mexico weakened slightly that day, allowing the cyclone to shift north slightly in its path. As a result, the center entered the Bay of Campeche during the afternoon of that day, and thunderstorm activity soon recovered near the center.