13 cyclones attaining tropical depression status,

13 cyclones attaining tropical storm status,

5 cyclones attaining hurricane status, and

4 cyclones attaining major hurricane status.

Before the beginning of the season, I predicted that there would be

15 cyclones attaining tropical depression status,

13 cyclones attaining tropical storm status,

6 cyclones attaining hurricane status, and

3 cyclones attaining major hurricane status.

The average numbers of tropical storms, hurricanes and major hurricanes (over the 30 year period 1991-2020) per season are 14.4, 7.2, and 3.2, respectively. My forecasted numbers were close to the final outcome in all categories. This season fell just below average in number of tropical storms and hurricanes, but notably had several very intense hurricanes, including three category 5's. The (preliminary) total Accumulated Cyclone Energy for the 2025 season is 132.6 units, which modestly exceeded the 30-year climatological average of 122.5.

The near-average total activity during the 2025 season is consistent with the mixed bag of atmospheric and oceanic indicators discussed in the pre-season summary. As forecast, ENSO neutral conditions prevailed through the entire hurricane season, with neither an El Niño nor a La Niña event active to suppress or enhance cyclone activity. As in the previous few years, Atlantic sea temperatures were well above the 30-year average, though the anomalies did not match the extreme ones of 2023 and 2024. The impact of these high ocean temperatures mainly lay in boosting hurricanes' intensity: despite having relatively few cyclones, 2025 featured a remarkable three category 5 hurricanes: Erin, Humberto, and Melissa. This was only the second time in recorded history that the Atlantic saw more than two category 5 hurricanes, after 2005 (which had 4).

Erin and Humberto reached category 5 strength over the western tropical Atlantic, an unusual feat made possible by ocean heat content reaching values usually only seen in the Gulf of Mexico or Caribbean. Finally, exceptionally warm waters in the western Caribbean allowed Melissa to become one of the strongest tropical cyclones ever recorded, reaching peak sustained winds of 185 mph winds and a minimum pressure of 892 mb on October 28. In terms of pressure, Melissa tied for third most intense among recorded Atlantic hurricanes, and was the strongest storm globally in 2025. Its landfall in Jamaica at 892 mb was tied for the lowest ever for a landfalling hurricane with the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane in the Florida Keys.

The map above shows all tropical cyclone tracks for 2025. It's notable that, with the glaring exception of Melissa, the south and west areas of the Atlantic basin were very quiet. In particular, the continental U.S. and Mexico each had only one Atlantic tropical storm make landfall. My area-specific forecast underestimated the risk to the Caribbean islands, and overestimated it elsewhere. The fortunate fact that most hurricanes went out to sea can be chalked up in part to a persistent pattern of upper-level troughing near the U.S. southeast.

The map above illustrates the upper-atmospheric pattern during peak hurricane season (August-October), highlighting lower than normal pressures over the U.S. southeast. This pattern generated flow from the southwest pushing hurricanes northeast out to sea, away from major landmasses.

A strange feature of the 2025 season that was repeated from 2024 was a lull in activity right at the climatological peak of hurricane season! This year, no named storms formed between August 24 and September 16 (compare to last year's lull between August 13 and September 9, which was even starker compared to the overall busy season). The last time no named storms formed in this date range is 1992, and before that 1939. A combination of features was responsible, including a regime of high sea-level pressure over the subtropical Atlantic (see below).

The map above shows a consistent high pressure area over the subtropics (red) in late August through mid-September. In the northern hemisphere, air flows clockwise around such high pressure areas, so cool and dry air from the northeast Atlantic was pushed down into the tropics, stifling the development of tropical waves coming off of Africa. Coupled with a high shear environment in the Caribbean during these dates, this effectively shut down hurricane activity.

Some other notable facts and figures from 2025 include:

- Tropical Storm Barry's remnants contributed to a devastating flash flood event in Texas on July 4-5 several days after its dissipation

- Hurricane Erin tied for the third-largest 24-hour pressure drop recorded in an Atlantic hurricane, dropping 83 mb from 998 mb to 915 mb on August 15-16 (the number one spot still belongs to 2005's Hurricane Wilma, the strongest Atlantic hurricane on record)

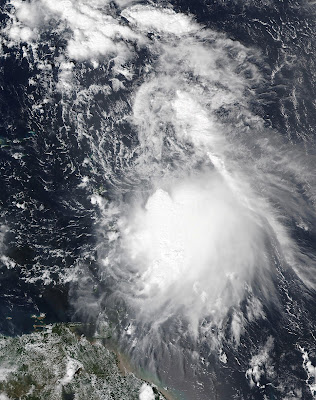

- Hurricanes Humberto and Imelda came close enough together to undergo a binary interaction, which altered the course of each hurricane (see the satellite image below); in fact, the minimum distance between the centers of the cyclones on September 30, around 466 miles (405 nautical miles, 750 kilometers), was the smallest recorded between two Atlantic hurricanes during the satellite era

- Subtropical Storm Karen was named at 44.5°N, the farthest north any Atlantic cyclone had been named

The satellite image above shows the interaction between Humberto and Imelda, which had the fortunate consequence of pulling Imelda eastward out to sea before it could make landfall in the U.S.

Overall, the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season had total statistics near the recent average, hiding the fact that it also had several exceptionally strong hurricanes.

Sources: "ENSO: Recent Evolution, Current Status and Predictions" from the Climate Prediction Center, CSU Department of Atmospheric Science Real-time Tropical Cyclone Activity, CSU Summary of 2025 Tropical Cyclone Activity, "2025 Atlantic hurricane season marked by striking contrasts" from the NOAA, Yale Climate Connections: "A Cat 4 and 5 extravaganza: A look back at the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season", Hurricane Humberto Tropical Cyclone Report (NOAA),